We huddled in a group next to the helicopter pad: a bare patch of red earth surrounded by an impenetrable wall of lush jungle foliage. The hypnotic hum of insects added a rhythmic pattern to the heat waves rising visibly in the tropical sun. The small group consisted of graduate students, postdocs and professors from across Europe and America, awkwardly navigating islands of conversation that, as soon as they appeared, sank back into distracted silence. We were all a little nervous at the prospect of the adventure ahead: helicoptering into a remote tropical jungle in French Guiana with a group of total strangers. Our attempts at conversation were soon swallowed up as the distant thrum of the helicopter engine quickly become a deafening roar. As it approached, the force of the propellers sent debris swirling into the air around me. I grabbed my backpack (a little too tightly) and marched towards the open door. The pilot gave a thumbs up as we buckled ourselves in, and deftly maneuvered the helicopter skyward. The patch of red earth shrank below us and was rapidly swallowed by an unending sea of jungle canopy - a stark reminder of just how isolated we would be for the next 7 days.

The Metabarcoding School, now in its 8th year, is the brainchild of the metabarcoding.org editorial board, namely Pierre Taberlet and Eric Coissac. The course includes lectures and practicals designed to introduce the fundamental techniques required for conducting DNA metabarcoding experiments. DNA metabarcoding uses molecular techniques (PCR and high throughput sequencing) to assess biodiversity from environmental DNA and bulk samples. This technique requires an understanding of molecular biology, bioinformatics, biostatistics, and ecology, and can be applied to address a wide variety of ecological questions. Topics range from biodiversity monitoring, to animal diet assessment, to the reconstruction of paleo communities. Each year, the workshop is held in a different remote location. This year’s workshop was co-organized by the Center for the Study of Biodiversity in Amazonia (CEBA) and the metabarcoding.org team (Eric Coissac, Pierre Taberlet), held at the Nouragues Scientific Station. The Nouragues Natural Reserve is located in central French Guiana, and comprises 76,910 hectares (190,000 acres) of pristine tropical rain forest. It’s one of the most bio-diverse places on Earth. Two research stations, administered by the CNRS (Centre Nationale de Recherche Scientifique), offer researchers the opportunity to explore this ecological paradise. The Inselberg Camp (where we stayed) sits at the base of the Inselberg des Nouragues, a spectacular 420m granite mountain.

The Metabarcoding School, now in its 8th year, is the brainchild of the metabarcoding.org editorial board, namely Pierre Taberlet and Eric Coissac. The course includes lectures and practicals designed to introduce the fundamental techniques required for conducting DNA metabarcoding experiments. DNA metabarcoding uses molecular techniques (PCR and high throughput sequencing) to assess biodiversity from environmental DNA and bulk samples. This technique requires an understanding of molecular biology, bioinformatics, biostatistics, and ecology, and can be applied to address a wide variety of ecological questions. Topics range from biodiversity monitoring, to animal diet assessment, to the reconstruction of paleo communities. Each year, the workshop is held in a different remote location. This year’s workshop was co-organized by the Center for the Study of Biodiversity in Amazonia (CEBA) and the metabarcoding.org team (Eric Coissac, Pierre Taberlet), held at the Nouragues Scientific Station. The Nouragues Natural Reserve is located in central French Guiana, and comprises 76,910 hectares (190,000 acres) of pristine tropical rain forest. It’s one of the most bio-diverse places on Earth. Two research stations, administered by the CNRS (Centre Nationale de Recherche Scientifique), offer researchers the opportunity to explore this ecological paradise. The Inselberg Camp (where we stayed) sits at the base of the Inselberg des Nouragues, a spectacular 420m granite mountain.

During the course, our time was split between lectures, round table discussions and hands-on practicals. We learned the major components of a basic metabarcoding workflow, from experimental design to bioinformatics, through ecological analyses. Lecturers Frédéric Boyer and Lucie Zinger provided more in-depth exploration of a bioinformatics pipeline (OBITools). Lectures and practicals always included a healthy dose of caveats and “lessons learned”, an important component of this type of work that is sometimes glossed over, even in publications from major journals.

During the course, our time was split between lectures, round table discussions and hands-on practicals. We learned the major components of a basic metabarcoding workflow, from experimental design to bioinformatics, through ecological analyses. Lecturers Frédéric Boyer and Lucie Zinger provided more in-depth exploration of a bioinformatics pipeline (OBITools). Lectures and practicals always included a healthy dose of caveats and “lessons learned”, an important component of this type of work that is sometimes glossed over, even in publications from major journals.

Occasionally, we were distracted from the intense coursework and reminded of our unique surroundings. It’s hard to focus on your computer when a troupe of capuchin monkeys decide to crash the party! We took night hikes through the forest, spotting caiman, scorpions, tarantulas, snakes, poison dart frogs, howler monkeys, and a wealth of insect diversity. One morning, we hiked to the summit of Inselberg des Nouragues, arriving just in time to watch the sunrise. It was a breathtaking view. As the pink glow of sunrise spread slowly over the misty canopy, stretching out endlessly in all directions below us, a cacophony of tropical birds stirred to life, serenading our vista. I decided that the view alone was worth the trip.

All too soon, the week came to an end. We unstrung our hammocks, folded up our mosquito nets, and packed them into our backpacks. The helicopter took us down to the lower camp at Saut Pararé, situated just below a series of high rapids on the Arataye River. From there, we boarded pirogues (motorized canoes) and set off on the 4-hour trip downstream. The river itself was broad and shallow, alternating between stretches as smooth and still as glass, and rocky rapids which required all the skills of our pilot to navigate. The heat combined with the sound of rippling water was just beginning to lull me to sleep when one of the other students gasped audibly. “I think I saw something… slithery”, she whispered. The pilot slowed and turned the boat around. As we approached the shore, we all spotted the source of the slitheryness. An anaconda, full from a recent meal, looked up from her sunny spot on the riverbank and regarded us warily. It was the biggest snake I’d ever seen, outside of a vivarium. She was easily nine feet long. “Un petit!” smiled the pilot. Apparently he was not as impressed as the rest of us were.

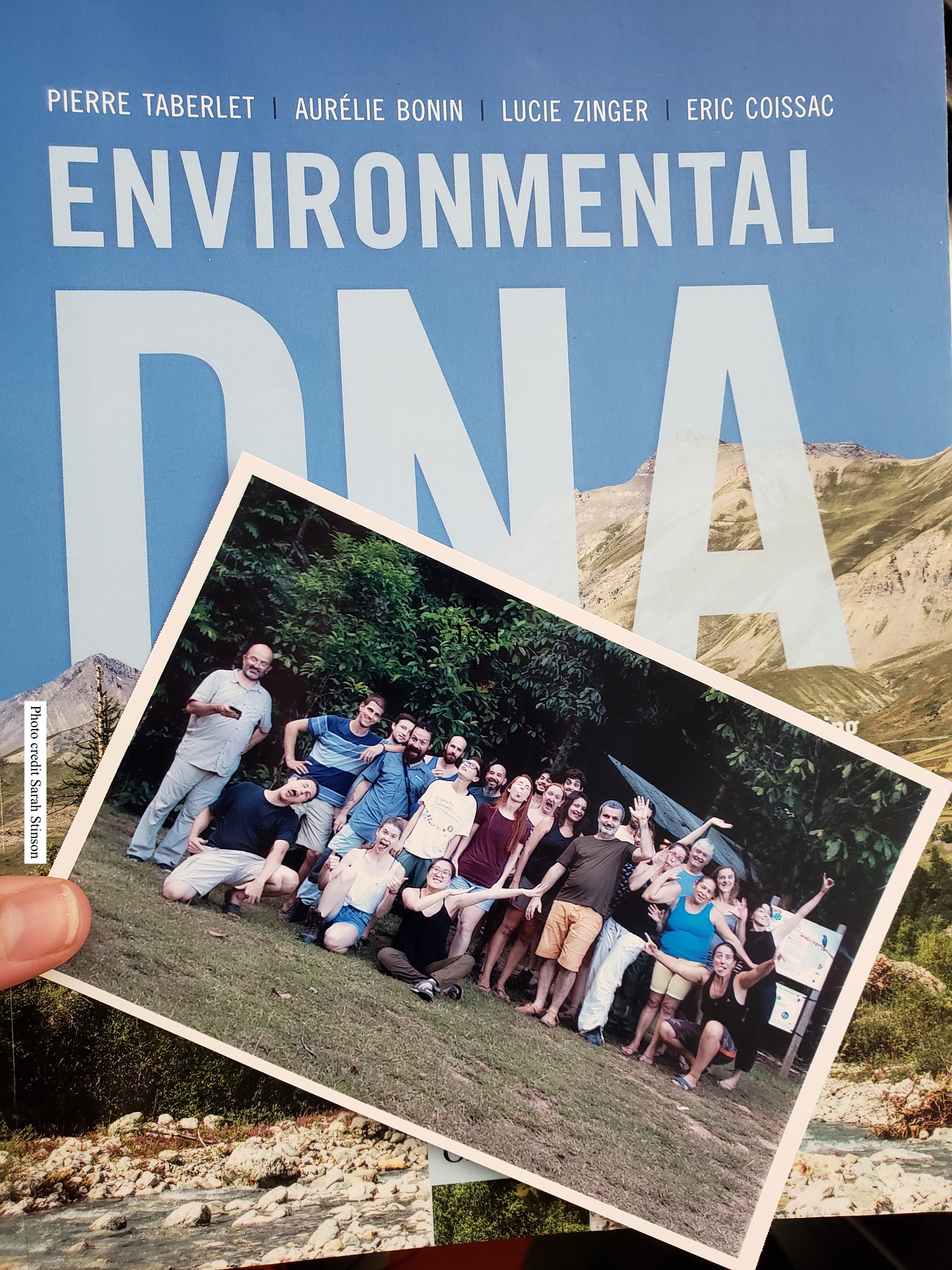

As I sorted through my notes from the course, wrapped in the glow of a semi-jetlagged, sleep-deprived haze, I came across a group photo taken on the last day at the station. In the photo, we’re laughing and completely at ease – the perfect appearance of a well-oiled team. Beyond the course material and the exotic destination, equally valuable are the personal and professional connections that we made. Yes, it sounds completely cheesy, I know. Then again, how often do you get to hang out with an editor of Molecular Ecology, discussing your research while drinking caipirinhas and watching howler monkeys?

As I sorted through my notes from the course, wrapped in the glow of a semi-jetlagged, sleep-deprived haze, I came across a group photo taken on the last day at the station. In the photo, we’re laughing and completely at ease – the perfect appearance of a well-oiled team. Beyond the course material and the exotic destination, equally valuable are the personal and professional connections that we made. Yes, it sounds completely cheesy, I know. Then again, how often do you get to hang out with an editor of Molecular Ecology, discussing your research while drinking caipirinhas and watching howler monkeys?

-Sarah Stinson